|

Diane does not look like someone who would drug your venison chilli. She sits on a San Francisco patio, her dewy blue eyes lucid, her blonde, subtly asymmetrical hair recently trimmed, her white jeans spotless. It is noon. I imagine she has enjoyed several fruitful meetings. Now, she will probably advise me on the meditation app keeping her serene.

“I don’t do coffee, I do acid,” she says. The declaration that she takes a Class A drug does not distract her from nibbling a chunk of salmon in her taco bowl. The 29-year-old start-up founder began microdosing LSD — tiny doses every few days — in January. At just a tenth of a tripping dose, she does not experience psychedelic effects. Rather than swirling in a magical universe with pink elephants, she says microdosing has improved her productivity, creativity and helped her focus. On LSD, she is able to concentrate when developing company strategy, speed through user design sessions and sparkles making new contacts. I met the microdosers and the old hippies for this FTWeekend magazine feature on how Silicon Valley has rediscovered LSD. I chose LSD as a way of telling the story of how San Francisco is changing and the conflict between millennial tech workers and the baby boomers who made the city famous. Read more here.

1 Comment

Sitting in the sunny garden of The Battery — the “see and be seen” private club for a San Francisco tech crowd that doesn’t care too much about how they look — Nicole Quinn, a partner at venture capital firm Lightspeed Venture Partners, told me about her plan to get out of the bubble chattering away around us. How? By taking a road trip across the US.

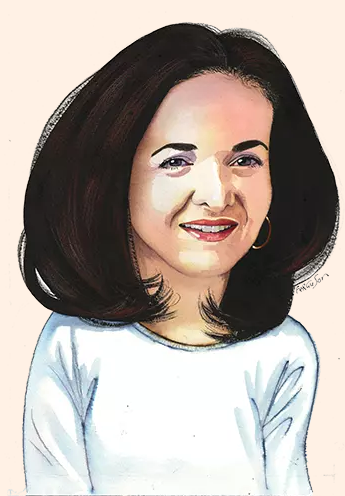

Snap-happy tourists have long posed next to the billboard-sized “Like” sign outside Facebook’s headquarters, in awe of seeing the real-life company behind the app. But it has taken until 2017 — and a political situation the tech industry sees as a crisis — to get Silicon Valley truly interested in the real lives of its users. I write regular columns for the FT magazine on the culture of the tech industry. Read more on 'How Silicon Valley discovered the rest of America' here. Other columns include the world of the Valley intern, ageism in Silicon Valley and how Peacetech is helping refugees. Dressed in a long white jumper over pale blue jeans, with her black hair blow-dried into a shiny shell, Sheryl Sandberg looks — as ever — supernaturally composed. She bounds up to hug me then takes the chair next to me at the corner of our table. “Check this out. Do you see this?” she says, studying the menu without pausing for small talk.

Facebook’s chief operating officer is famous for being more open than most executives: about crying in the bathroom at work, or how, as a recent widow, she slept in the same bed as her mother. This is fitting for a company that has redefined the word “sharing”. As we settle into our lunch, however, it is clear openness does not exactly mean spontaneity. Sandberg has to be one of the most on-message executives. Talking about business, she uses such a set phraseology I can almost recite her lines for her. New products are not only in “early days” but being introduced in a “privacy-protected way”. When, at one point, I ask her how she could best describe what it is like to suddenly be a single parent, she confesses it is “lonely, scary sometimes”, then briskly broadens her point to include the plight of poorer single mothers across the US — with statistics. I interviewed Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg for the FT's most famous interview slot, the Lunch with the FT. I asked her about Facebook's growing power in the world, her grief at losing her husband and her dating advice for young, ambitious women. Read more here. In chalets scattered across the snow in California’s ski country, a school of the future is taking shape. Warm inside a classroom, teenage twins Laurel and Bryce Dettering are part of a Silicon Valley experiment to teach students to outperform machines.

Surrounded by industrial tools, Bryce is laying out green 3D-printed propellers, which will form part of a floating pontoon. The 15-year-old is struggling to finish a term-long challenge to craft a vehicle that could test water quality remotely. So far, the task has involved coding, manufacturing and a visit to a Nasa contractor who builds under-ice rovers. “I suck at waterproofing. I managed to waterproof one side, did a test of it, it proved waterproof. I made sure the other side was waterproof, put both sides on and both of them leaked!” he laughs. Laurel, already adept in robotics, chose a different kind of project, aimed at developing the empathy that robots lack: living on a reservation with three elderly women from the Navajo tribe. “The experience was just, honestly, it was really . . .” she trails out, her navy nails fiddling with her dark-blonde hair. “They didn’t have running water, didn’t have electricity, they had 54 sheep and their only source of income was weaving rugs from wool.” The Detterings have embraced personalised education, a new movement that wants to tear up the traditional classroom to allow students to learn at their own pace and follow their passions with the help of technology. Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, and his wife Priscilla are leading the push to create an education as individual as each child, aiming to expand the experiments beyond the rarefied confines of Silicon Valley. An FTWeekend magazine front cover on Silicon Valley's obsession with personalised education. Philanthropists including Mark Zuckerberg believe technology can help students move at their own pace and pursue their own purpose. Read more here. |

AuthorA selection of my work covering technology for the Financial Times' global audience. Archives

December 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed